In early 2003, the drumbeat of a war was reaching a fever pitch and things in Mauritania were getting tense. We’d been preparing mentally to be evacuated ever since September 11. In the weeks just after the attacks, when we were all huddled together at the maison in Nouakchott, a fellow volunteer known for histrionics (you know who you are! lol) burst into a room where we were playing mafia or some such thing and said, “I just heard from the bureau! The US has bombed Damascus and we’ve been ordered to evacuate. Time to pack your bags!”

We all believed him. That was exactly how it was going to happen.

Eighteen months later, it did happen, only it wasn’t Damascus getting bombed but Baghdad. In the end we weren’t evacuated, but I believe we came close. Things certainly got a little wild.

We all thought we’d be sent home once the war started, and we’d been waiting for it for a long time. The BBC World Service reported each fractional step closer to war for months. That was my early-21st-century version of doom scrolling: breaking out my shortwave radio every hour on the hour to take part in the slow build toward catastrophe. While we expected protests borne of Arab solidarity and latent anti-Americanism, the only aggression I witnessed was an old lady cursing me and spitting at my feet. Was that because of Iraq? Hard to know.

Nonetheless, on March 18 armed local police started guarding our homes in Aioun. The next day, when the bombing began, the police started following us around town, which made visiting people or going to the market a little awkward. It didn’t last long. The head of police for the region or town decided to consolidate all the foreigners together. The Germans all went to a German expat’s place; the French and Americans all went to a French expat’s. Believe me, there were worse places to be. We already knew his place very well. We’d gather there for dinner parties, to swim in his pool, to drink and smoke cigarettes, and to watch TV. It was a decadent, epicurean oasis.

We were in our decadent house arrest for nearly a week when things got weird and uncanny. At first, it was just us four Peace Corps volunteers and one of the French volunteers, enjoying the hospitality of our gracious host. Then another French volunteer showed up. Then a French guy on a motorcycle showed up. Then two Swedish tourists showed up. Basically, any non-German foreigner passing through Aioun—usually a rare event!—was put under house arrest with us. We nine uninvited houseguests lived together for a few days, vying for sleeping space, sharing wine, hoping to wait out the threat so that we could go our various ways.

Our momentary life of luxury wasn’t exactly without care. In general, I was ready to go. I’d basically completed my service. But specifically, there were a lot of things I hadn’t done. I didn’t have many souvenirs; I had no pictures of my students; I had had no closure with anyone I would have wanted closure with. Despite the pool and the booze and other comforts of my enclosure, it was stressful to see my service potentially end with such a whimper. Plus one of the French guys came down with malaria, left to go to the hospital, and came back later, IV bag in tow, to sleep off his fever for a few days. Fun times.

After four days the Wali decided that the Americans should go to Nouakchott. He called the bureau to ask them to get us out of Aioun, and they agreed to either charter a plane or have us get on the next commercial flight to the capital. For some reason the plane never showed up, and it was a few days later before a Peace Corp vehicle arrived with its logos long ago removed. We were to leave town at 4:30 the next morning to avoid trouble.

My memory of what happened next is dim. My journal skips 10 days. My next entry is a largely illegible poem about doubt, confusion, and frustration rising from a romantic pursuit, which means that we volunteers were together again in Nouakchott. A few days later the option was out: for the second time during my service (the first was after September 11) any volunteer who wanted to leave Mauritania (early terminate) could do so without repercussion and perhaps continue their service elsewhere. At that point I only had less than two months to go, so I stayed.

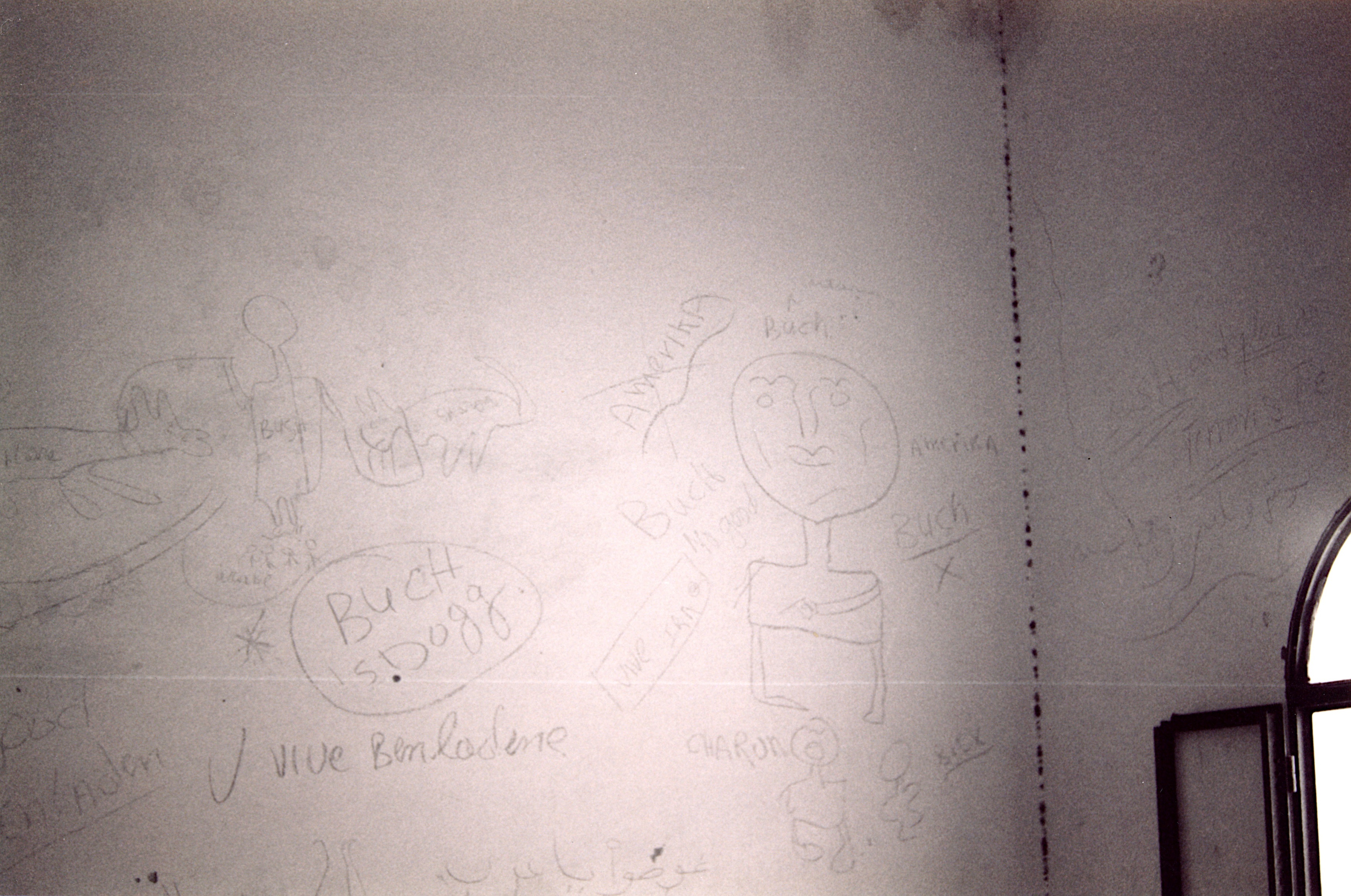

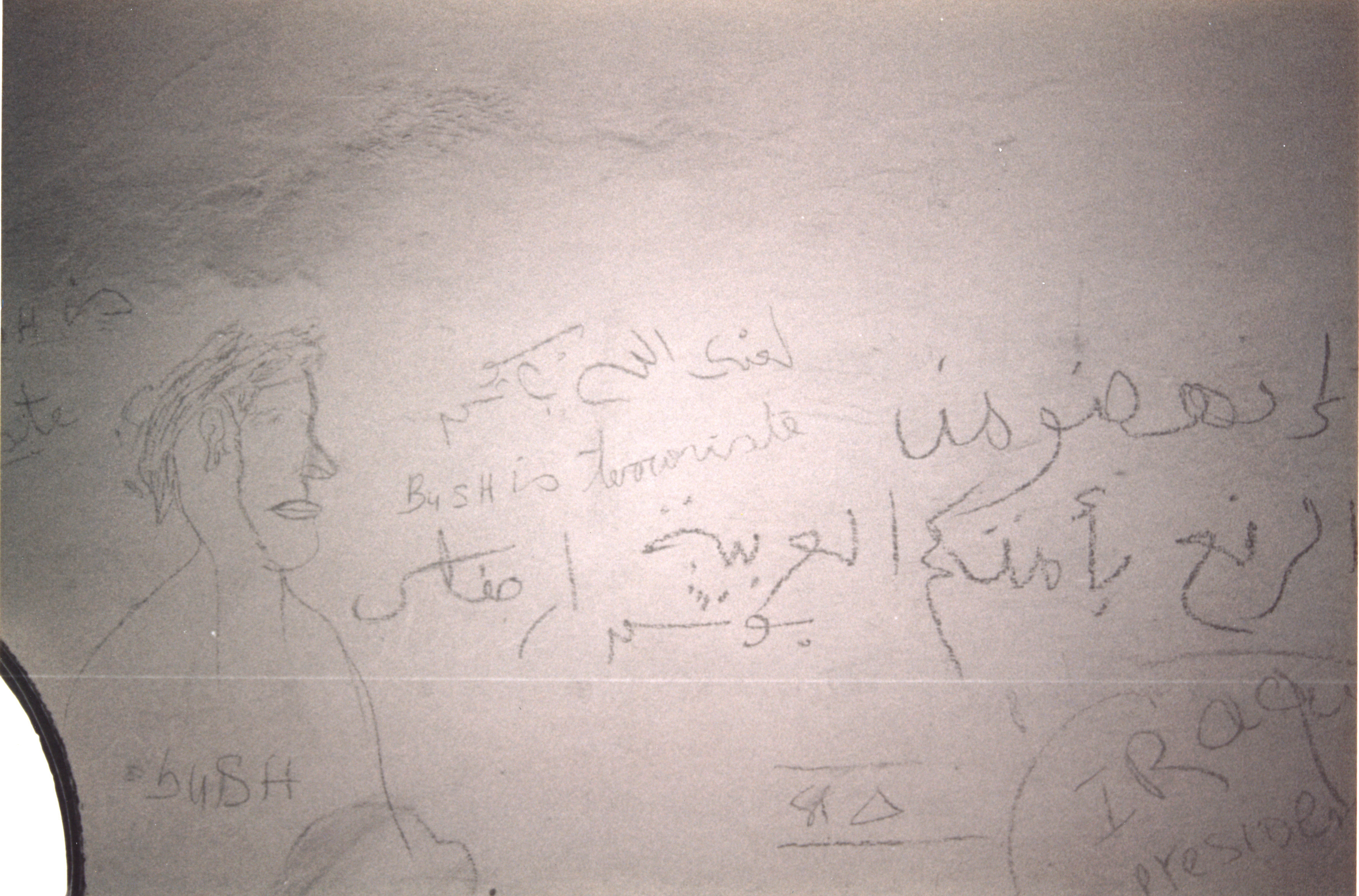

I returned to Aioun around April 22. Protests and threats in response to the invasion of Iraq never amounted to much. It was good to be back, to get back to my routine and to teaching, and to trying to do Peace Corps in a time of war. I don’t know what my students did while I was gone, whether a fellow teacher covered for me or if the kids just had some extra free time, but there was some extra writing on the wall, caricatures of George Bush and graffiti calling him a dog. I didn’t disagree but I pretended not to notice.

The next weeks—my last weeks—went quickly. I witnessed no further aggression or protests. My students were nice and thankful that I tried to teach some of them English. They, like most people, could like a person and disdain their government without suffering cognitive dissonance. Perhaps my presence tempered some ill will toward my country. Perhaps it heightened it. I don’t know.

Either way, on May 31, 2003, my mission really was accomplished.

May 31, 2003I just woke up: my last full day in Aioun. It rained last night, the first thing past a drizzle for the season. I woke from the wind and saw nothing in the sky. An ominous dark shielding the usual night glow. The possibility of rain didn’t cross my mind; I fell back asleep to awake sometime later to the drops on my forehead. Rain.

And it smelled like rain, too, like earth, like wet cereal.

The rain grew steady and the wind was blowing into the porch. I had to move all the way inside where it was too warm to properly sleep. I drifted in and out with new visions each time I closed my eyes. Flashlights in the yard, a woman in bed, my homecoming back in the States.

I awaken to quiet. The rain has slowed. I move back out to the porch where the breeze is pleasant and cool. It’s dark, nearly completely so, and I go to fill my buckets for bath and drinking water. It must be near 4 a.m. The water comes pretty strongly.

Replete, I stumble back to my matela and collapse. Soon the sun comes. Then the flies, then the goats, and I have no choice but to begin my last day in Aioun.